“There’s no such thing as race.”

Do you agree?

I agree.

I confess too.

In a fit of anger or frustration, whether with myself, or some-one around the corner, I have cussed. It comes down to my frailties as a human being, but I’m not offering this as an excuse. Fingers are pointed daily towards those who harm others who are invariably (physically, economically) weaker. And accusations are made. You are a racist. What defines a human being as a racist? Well, we now know that we don’t need to search very far to find the answer. And, if we’re honest with ourselves, we can find out if we are truly non-racist or not.

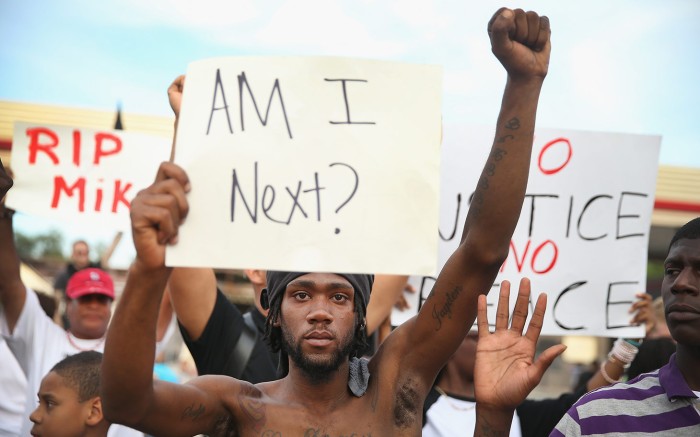

This thorny question is not the subject of this post. But it is related. I confess once more. I have not made any further close readings beyond Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, Beloved. Since I first blogged about my readings of this haunting novel over a year ago, things seem to have gotten worse. And Morrison’s novel becomes more relevant to our present just as it remains in our tortured and cruel past. I am left wondering what Ms Morrison makes of events across America these days. These events, as you know, started with the tragic shooting to death of an African American civilian by a cop. The killer has been accused of being racist.

Morrison, it needs little reminding, won the Nobel Prize for literature as far back as 1993. She has written a number of novels since then. But, I may be wrong in saying this, I do not think any of these works that followed Beloved have matched or surpassed the stories of Sethe, Denver and Paul D. And Beloved. These phenomenal stories also stretch way beyond the hurtful consequences of racism. A young American recently posted an excellent essay on his blog reflecting on and telling the true story of the events leading up to America’s declaration of Independence from Great Britain. Any (black) African American who is acutely familiar with his or her family tree will tell you (and me) that their forefathers were there and rebelled against the British who could not see their way past allowing the colonists’ desire to decide their own destinies independent of the British Empire.

I had to ask this talented young man just one question. During the process of fighting for independence, how many indigenous Americans lost their lives and lands. It’s a small world. But, fortunately the people whose ancestors were indigenous to the Southern tip of Africa still have a say in deciding their destinies. That their means are limited or challenging is a story for another day.

Although it is indicative of a single novel, I still regard Toni Morrison as one of my favourite authors. I remain in awe of her range, vision, sense of history and the feelings that she pours into this single text. Morrison’s feelings go beyond the talked about problems of racism. It tries to delve into the heart and mind of a rapist. It remains a voice of solidarity for the oppressed, particularly women. But it is never feminist. Ms Morrison once said the following when talking about the pain of being raped;

“Rape is a criminal act whatever the circumstances. A woman riding the subway nude may be guilty of indecency, but she may not be raped. If she invites or even sells sex at 10 and refuses it at 10:45, the partner who disregards her refusal and forces sex is guilty of rape. If she is drunk, asleep, mentally defective, paralyzed or dead, she must not be raped. Why? Because sexual congress must be by consent.”

Even though rape is outlawed in most countries where the rights of women, children and men are preserved in law, it is still practised as though it were merely a game. Like a cat playing with a meek mouse.

On racism, she had this to say;

“I always looked upon the acts of racist exclusion, or insult, as pitiable, for the other person. I never absorbed that. I always thought that there was something deficient about such people.”

I could not agree more. And what about the way we talk to each other nowadays? Particularly when we are angry. “Oppressive language does more than represent violence, it is violence.” Even when we are ourselves violated or oppressed in unmentionable ways we too fall foul of our hurt and anger and join the vicious throng of hatred. It is a year since he passed away, but when pondering US President Barack Obama’s recent and weak suggestions on how to cure a great nation (and, indeed, the rest of the world) from racism, the life, work and words of Nelson Mandela remain alive to me. We know too that he follows the legacy of a great many men and women who have done more to heal and unite than to divide. Dr Martin Luther King, Jnr and Mohandas K Gandhi are two such men.

Toni Morrison’s novel, Beloved, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1988. In that same year, Alfred Uhry’s stage drama, Driving Miss Daisy, won the prize for drama. Both book and play were expertly adapted for the film screen and featured household names such as Opra Winfrey, Tandy Newton, Danny Glover and Morgan Freeman. I am also reminded of Alice Walker’s novel The Colour Purple, far more gruesome than Morrison’s Beloved perhaps. But ladled with hope. Steven Spielberg’s award-winning adaptation also marked the brilliant debut of a young Whoopie Goldberg.

“Terrible, unspeakable things happened to Sethe at Sweet Home, the farm where she lived as a slave for so many years until she escaped to Ohio. Her new life is full of hope, but eighteen years later, she is still not free.”

Sethe’s new home is not only haunted by the memories of her past, but also by the ghost of her baby, who died nameless and whose tombstone is engraved with a single word:

“Beloved.”

Today, not a single day goes by when a young policeman, or conscientious civilian has not discovered a foetus, or new-born, but dead baby, in some or another dumpster.

When I was initially asked to do a review of Beloved, these questions were asked; Is Beloved a ghost, a real woman, or the manifestation of Sethe’s repressed memory? It was possible to work out where Beloved came from and what she wanted from Sethe, Denver and Paul D. I was also asked to remark on the literary techniques that Morrison used to create feelings of uncertainty and ambiguity around the complex characters of Sethe and Beloved. An awareness of the story’s historical significance also needed to be made. Thus;

“Sixty Million…and more”

Morrison’s epigraph and foreword to Beloved give clear indications as to who or what Beloved is. Characteristically, she/it is multidimensional. Is she/it a ghost, a real woman, or Sethe’s repressed memories? It is open to us, as readers, to interpret. Sethe is Beloved’s mother. And Beloved is a ghost. Ambiguity, furthermore, allows us to decide on Beloved’s status. Beloved’s supporting character’s also react and relate to Beloved in different ways. The text is thus an open book.

Literary critic Marsha Darling puts it this way; “she is a spirit on one hand, literally she is what Sethe thinks she is, her child returned to her from the dead. And she must function like that in the text. She is also another kind of dead which is not spiritual but flesh, which is, a survivor from a true, factual slave ship.”

This analogy reminds me too of Steven Spielberg’s critically acclaimed interpretation of American slave history in Amistad, a film which I have yet to view closely. Nevertheless, I have recognised the source of Beloved’s existence to the inter-textual Biblical reference to Saint Paul’s letter to the Romans. It appears as a second epigraph in Morrison’s astonishing story;

“I will call them my people which were not my people; and her beloved which was not beloved.”

According to scripture, Paul talks about God’s patience with men and women. Startlingly, he mentions that only a few will be saved. But Toni Morrison responds to this. She alludes to bigoted (racist) white men and women who ludicrously believed that they were God’s chosen few. Recently, British director, Steve McQueen explored this self-same supremacist fallacy graphically in gruesome detail in his acclaimed adaptation 12 Years a Slave. These delusional white men and women believed that they had a divine and custodial stranglehold over the inferior “others” who lacked God and spirituality. Today, we know that was and is simply not true. And Baby Sugg’s characterisation as an unorthodox spiritual leader challenges these perverted beliefs of the white American land owners. Correctly, Morrison asks whether God has lost patience with “the chosen few”. Like US President Barack Obama, she uses the mantra of “Hope” in her prose. She believes that God will turn His divine will onto those who suffer and are persecuted the most by man’s evil and save them.

Initially, Morrison wanted to respond to the rights of women, and she foregrounds both demands and dilemma’s in Beloved;

“…equal pay, equal treatment, access to professions, schools…and choice without stigma.”

“To marry or not. To have children or not.”

Morrison’s mission statement leads to one of the most profound inter-textual literary references to history that I have come across. The creation of her character Sethe is directly linked to “the historical Margaret Garner” who was “a young mother who, having escaped slavery, was arrested for killing one of her children rather than let them be returned to the owner’s plantation.” Cape Town-born poet, Finuala Dowling believes that Garner inspired Morrison.

Sethe’s lover, Paul D, believes that Beloved is a woman. Filled with fear, perhaps loathing as well, Paul D does not accept Beloved’s presence in Sethe’s rented home, 124. The narrative marks this rejection; “124 was spiteful. Full of baby’s venom.” We are never sure whether the black male slave who oppresses rather than consoles his female companion, is superstitious and believes that Beloved is a ghost. But Beloved, the ghost, takes the form of a human in order to realise her desire to be loved. Much like God giving the world His one and only Son, because He loved the world so much.

But, as a ghost, Beloved remains a “repressed memory” to Sethe. Such a claim is important, because memory is the story’s main theme. Let us return to Morrison’s introduction “Sixty Million and more.” The introduction acutely alludes to the devastating effects of slavery on African Americans, their peers and their African descendants. Morrison argues that it is not possible to forget such tragedies. She also concedes that the pain of remembering this past is unbearable to the point that it may be better to forget the past. But we now know, too, that it remains important to remember the past in order to heal or achieve justice and equality.

Witnessing present events which did not begin in Ferguson, we can see why this is important. Tragically, the human condition buries terrible traumas deep in the psyche until it is yanked out once more. This is Beloved’s role. Sethe wants to believe that her child has been brought back to her and that she has been forgiven. But her act of infanticide, like abortion, equates to murder of the innocent. And it remains difficult for Sethe to endure the cruelty of her “white owners.”

It is never difficult for the reader to follow this linear story which begins with introductions to Sethe, Denver and Paul D at 124. Narrative time is also shifted to allow us to trace Beloved’s roots. This is never confusing even when we are led to believe that Beloved is a reincarnation of Sethe’s mother. The importance of Baby Sugg’s character shows how Beloved can be used to trace Sethe’s origins. Still delusional, Sethe believes that her dead mother has sent her child back from “the other side” which can be interpreted as the dark, hollow middle ground between Heaven and Hell and a place where the restless dead wait impatiently for the Day of Judgement. Purgatory, in other words. Alternatively, Beloved’s return to her mother can be a day of redemption. Unfortunately, there is no reconciliation between mother and daughter.

As a supernatural being, Beloved aims to help her mother come to terms with her actions. Even though she never does, Sethe still claims her daughter;

“Beloved, she my daughter. She mine. See. She come back to me of her own free will and I don’t have to explain a thing.”

This is tragic. Sethe never comes to terms with her tragic past and deeds. She never finds peace. She loses her mind. No longer useful, Beloved leaves her mother and returns to the place where the dead wait.

And yet there is still hope. Denver, always wary of her mother, finds peace. She becomes a beacon of hope for the black, emancipated women of the future. She finds peace of mind. She learns “book stuff”. She gains meaningful employment in order to support her demented mother. Denver remains aware of her dead sister, where she comes from, why she came, and why she has left.

Difficult as it may be, Paul D’s actions are plausible in light of the characters’ circumstances. But his actions are a warning to women that they are never entirely free from their own bondage (as women).

Morrison’s defamiliarising technique is powerful when she dismisses the white race. The ruthless “schoolteacher” is always referred to in lower case type to emphasise his status as an insignificant sub-human in contrast to his treatment of black slaves. She references white men as “men without skin”. What a haunting metaphor! The post-colonial method is turned on its head and the white colonist becomes “the other”, a strange, unfamiliar pale human who is without strength and courage.

Ultimately it is all about love and acceptance. Beloved wants love from Sethe. Beloved wants friendship from Denver. She wants Paul D to recognise her for who she is. As a ghost she can be a malevolent creature too.

I had to wonder still what the Nobel Laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Toni Morrison had to say about the recent events of racism plaguing the USA today. When she appeared on The Colbert Report last month, Morrison had this to say;

“There’s no such thing as race. Racism is a construct. A social construct.”

Pingback: Beloved by Toni Morrison – Institutionalized Racism